It was the summer of 1994 and I was back in the states after a decade spent covering bloody clashes in the Middle East and the turbulent collapse of Communism in the Soviet Union when I first heard the news about Kevin Carter. I already knew him as a member of the Bang Bang Club - a group of photojournalists based in South Africa and notorious for their often-reckless coverage of apartheid's final deadly days. I'd seen his Pulitzer-winning photograph, published by the New York Times, which personified the heartbreak of the Sudanese famine with the image of a tiny girl squatting on scrawny knees, head drooping heavily to the ground, a vulture lurking behind. The image haunted me, in part, because the girl was close to the age of my own daughter. Close to the age of Carter's daughter, as well.

Photo by Kevin Carter

Photo by Kevin Carter

I wasn't prepared for the news of that July. Two months after he'd collected what he'd called the highest acknowledgment possible of his work, and had been feted and praised, Carter parked his red pickup truck near a small river where he used to play as a boy, attached a garden hose to the exhaust pipe and gassed himself to death. "The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist," he wrote in a note he left on the passenger seat.

Word of his suicide came just as I was realizing for myself what covering a lesser degree of violence had cost me, so I understood pretty quickly that what might at first seem inexplicable, if examined for a moment longer, was not.

Journalists who regularly cover war pay a price. Stepping around those pointlessly killed in warfare, or interviewing someone who has just lost the one closest him, takes a toll. The typical penalty is a repression of emotions that begins, by necessity, in the field. This isn't initially a bad thing; in fact, at the time, it's crucial. The aftermath of combat often leads to the most profound moments in people's lives. In order to be fully present, journalists must shove their own shock or fear or revulsion into an inaccessible corner and ignore it - at least long enough to cover the story, maybe longer.

I remember the first time I came face-to-face with a body - a policeman sprawled in the middle of the road, killed during a domestic quarrel that turned into a triple homicide. I sneaked past police barricades, found myself standing next to another cop who turned out to be the victim's brother, and listened as he poured out his anguish - or, put another way, I exclusively collected the quotes that would land the story on front pages across the country the next day. As the congratulations rolled in, I felt nauseous and ashamed. I left town for the weekend, holed up with another journalist friend, and then decided I had to accept the predatory, voyeuristic aspect to the job I loved, or quit. So I suppressed my emotions, and kept smothering them as I witnessed bloodshed in Lebanon, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and interviewed victims of horrendous crimes.

The difficulty is that this skill of suppression, once honed, can impose itself on one's personal life. Those who have spent long months in war zones may find themselves reluctant to invest too fully in other arenas as well, shy about emotional involvement, stingy with their feelings. Then, the act of covering war can turn into what social critic Christopher Lasch has called "a refuge from the terrors of inner life."

Another repercussion of war coverage is a strange and growing compulsion to witness violence - the lust of the eye, as the Bible puts it - as well as a craving for the rush of risk-taking. It may seem contradictory, but it makes a mad kind of sense. In the midst of that death and destruction, the journalist can begin to feel invincible - in fact, maybe has to feel invincible in order to keep on - and that feeling is addictive. In my own experiences, I never really believed the fighting would claim me, even when the shooting was right there, even when I was stepping over spent bullets, swimming in tear gas or accosted by a furious, drunken Soviet soldier. I never bought the cliche about one's number eventually coming up. Yet sometimes I found myself palm-damp scared. And maybe that signaled an intuition I should have listened to, but I usually didn't have time, and I survived anyway, and there's an unparalleled, heady victory in that.

Of course, it requires more suppressing of emotions - in this case, fear.

The effects of covering war and near-war are not all negative; there is an almost ecstatic camaraderie in the shared experience of moments that those "back home" can never know. "We had shared something together in Sarajevo so intimate and incommunicable, a humility and compassion among individuals unconnected by blood tie, which I have never found elsewhere," Anthony Loyd wrote in his book My War Gone By, I Miss It So. In addition, covering conflict can offer a journalist a glimpse at a deeper humanity, one in which trivial concerns are recognized for what they are, and people pressed up against the wall really do the right thing.

Then there are the other times, when it seems no one is doing the right thing - not the participants, and not the watching journalists. Two months before he claimed the Pulitzer, Carter was among the photojournalists in South Africa who witnessed, from only feet away, the summary execution of white right-wingers by a black policeman. The photographers captured the fear on the victims' faces right before they crumpled and died. Then the photographers turned and ran. "Inside something is screaming, "My God,'" Carter said. "But it is time to work. Deal with the rest later. If you can't do it, get out of the game."

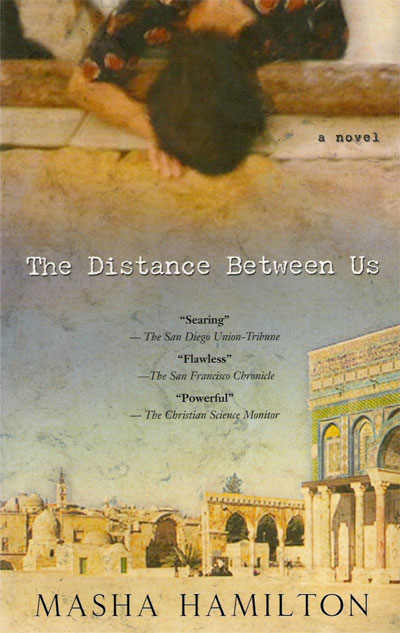

Deal with it. Dull your emotions. Carter didn't, in the end. This novel is dedicated to him, and other journalists like him who cover war and give up pieces of themselves to do so.